By way of introduction, I’m an altitude nerd. I moved to Boulder three years ago from sea level and have been obsessed with learning everything I can about altitude in order to play safely in the back-country. I bought the gear, taken the AIARE courses, I’ve even started a company specializing in altitude simulation!

Recently, while recreating at relatively high altitude, our group had to deal with a situation that I’d like to share. It’s one that I have been thinking about since and has caused me to make a few changes in my trip planning and altitude preparation kit. I share it here for your consideration and perhaps will help if you ever come to a similar situation.

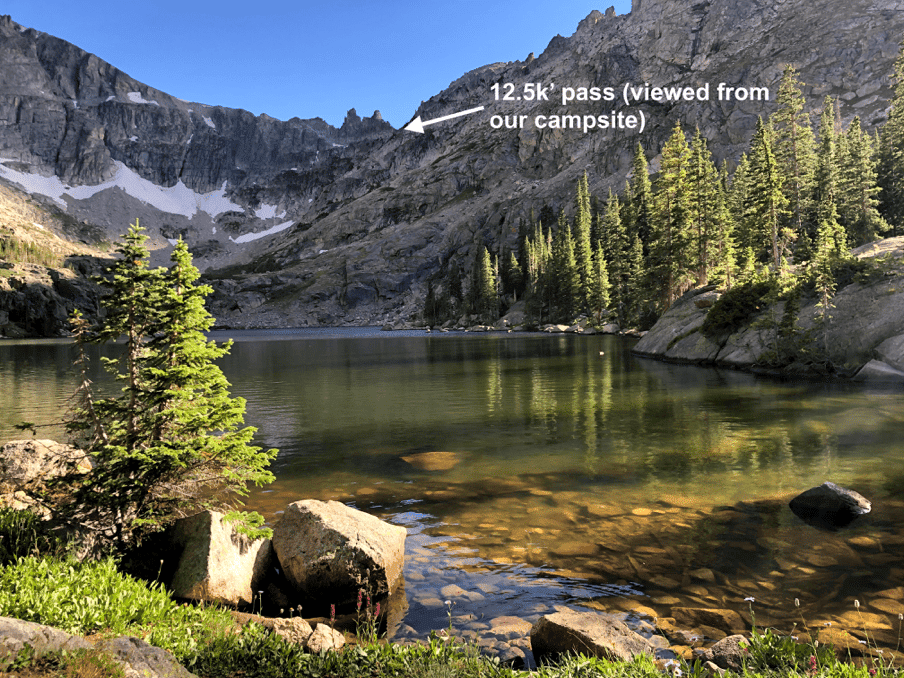

Our group was camping in the Indian Peaks Wilderness area at an elevation of around 11,000’. To get there, we had spent the day on a moderate 6-mile hike that took us up to 12,500’ with heavy packs. Everyone in the group was well fed, hydrated, and reasonably fit. Kim, a member of our party, certainly fit that description, in her early twenties and regularly active. However, she had only just flown in from the east coast two days earlier. She spent her first two nights in the Denver area at 5,000’. Shortly after making camp, Kim started experiencing a moderate headache along with some nausea. At that altitude, we understood this could develop into a serious situation.

Observing her closely, we noted she did not show signs of the “umbles” — the mumbles, stumbles, and bumbles that usually indicate High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE), a serious, life-threatening condition. Had that been the case, we would have pressed the SOS button on our emergency satellite device immediately.

She also did not have any shortness of breath or crackling lung sounds which are symptomatic of an equally serious condition known as High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE). With those two scenarios seemingly off the table, at least for the moment, several of us recognized her discomfort as acute mountain sickness (AMS).

So now what? We started thinking about our options in case her condition worsened.

Option 1 – Hike back the way we came to the east

This was the shortest way out, retracing our six-mile hike of the day before. The two benefits of this plan were the shorter distance and that our car was parked at the trailhead. The drawbacks were taking Kim back up to 12,500 feet over the pass via some fairly technical, class 4 terrain. Here’s what the distance and altitude profile looked like:

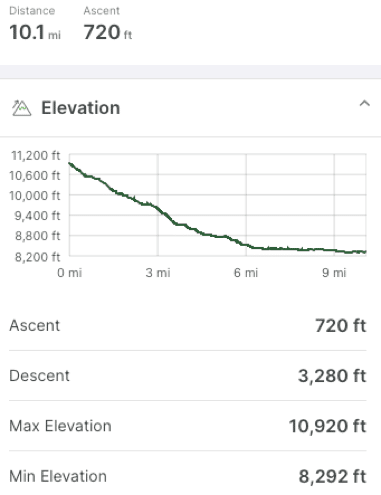

Option 2 – Continue hiking farther west to a well-traveled trailhead

This hike was 100% downhill and non-technical — very tempting since we knew it would be easy-going for Kim in her condition. However, it was a much longer, 10-mile hike and the distance would have been very challenging for Kim. Additionally, we had no transport waiting for us at the trailhead. Here’s the profile of what that exit looked like:

Option 3 – Call in the cavalry

We had several satellite communication devices in the group so calling 911 to organize an evacuation was also an option. It didn’t seem like we were quite there yet, so we put that on the back burner.

Option 4 – Medications

One of our group members was an experienced backcountry enthusiast and had a supply of Advil (ibuprofen), Diamox (acetazolamide), and dexamethasone in his first aid kit for exactly this purpose. While we were reviewing our exit strategy options, we administered the Advil and Diamox. Kim started to feel better within a couple of hours — so much so that the following day, she was able to do a relaxed day-hike from the camp. The day after that she hiked back the way we had come, over the pass, with no difficulty.

What Worked

Playing in the backcountry is an awesome, life-affirming experience. But it’s no joke. Any situation can turn dangerous in an instant and preparation is everything. Intentionally expanding your knowledge and understanding of the environment is essential — after this trip, I went straight to my family physician to add those drugs to my own first aid kit*. Ultimately everything worked out for Kim, but there was a lot of experience and knowledge to draw from in our group. Also, it was comforting to have the satellite communication devices ready to go in case we had to arrange an evacuation. Having something similar on-hand (fully charged, and knowledgeable in its operation) should be considered a must-have for anyone playing in the backcountry and outside of cell phone range.

*consult with your physician before taking or administering any medication

What Didn’t Work

The obvious error in this scenario was in the planning. Taking someone from sea level to camp at 11,000’ within a couple of days is a recipe for discomfort at best and has the potential for much worse. Ideally, Kim would have had more time to acclimatize in the front range below 6,000’ before heading up into the mountains. Given her lack of acclimatization, we should have selected a lower campsite with an easier approach.

Other Options?

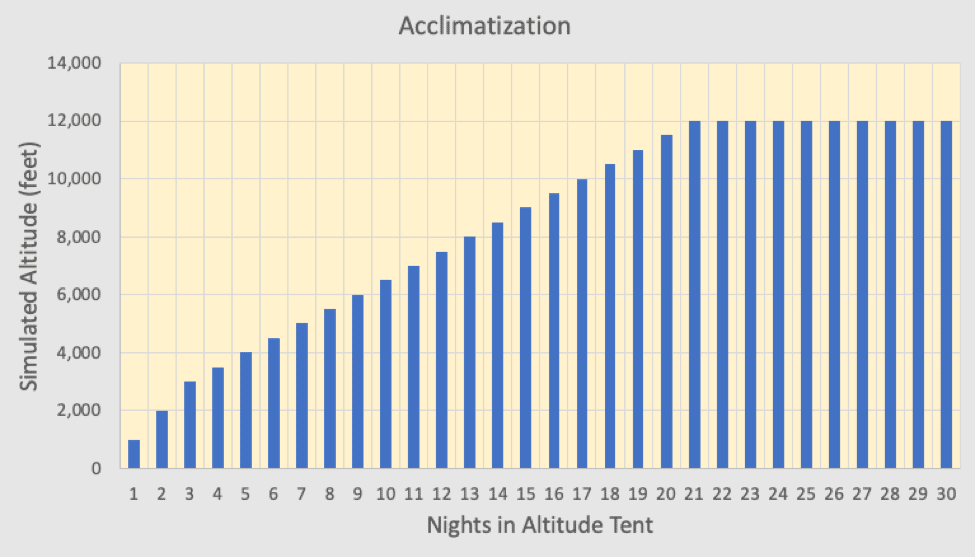

As I said, altitude simulation is what I do, so personally, I would recommend sleeping in an altitude tent before heading up to 11,000’. It’s easy to gradually increase the altitude day by day and help avoid the symptoms of AMS. The typical rate of altitude increase is 500-1,000 feet/day but some prefer to go up even more slowly than that. Even though I live in Boulder at an altitude of 5,600’, I sleep in the tent for the entirety of the back-country ski season. The extra bonus is that sleeping in a hypoxic environment stimulates your kidneys to produce EPO which ultimately improves your cardio capacity.

Regardless of whether the acclimatization occurs at real altitude or simulated altitude, the key here is to go up slowly. Additionally…

- Know the limitations of each person in your group and plan the distance and elevation of your trip accordingly

- Don’t get stuck in an “altitude trap” where you have to go up to get out

- Take the recommended safety and first aid gear

- Have a way to communicate when outside of cell-range

- Check the local weather and avalanche forecasts

- Have fun!

~by Jon Jonis, CEO of Mountain Air Health, maker of automatically controlled altitude simulation systems for cardio improvement, pre-acclimatization, and weight loss